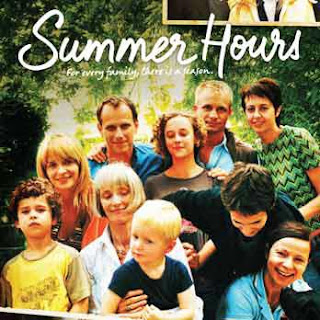

Bottom line: Brilliantly nuanced French drama about a family in transition

Grade (on a 1-10 scale): 9.5

“Of course YOU should see it,” said my friend Nicholas when I asked about the forthcoming French drama Summer Hours. Nicholas, an erstwhile Parisian cinephile of exacting tastes, and I had together seen one of Olivier Assayas’ previous films and been rather underwhelmed. When I asked him about this new one, which he’d caught in France, his response was tailored to his interlocutor: “YOU” meant “you, of all people.”

I soon learned why. Summer Hours concerns a storied old house and a family’s grown children trying to deal with their inheritance, which involves dilemmas that are at once emotional, cultural and financial. My documentary Moving Midway deals with the same subjects. Though one film is fiction and the other nonfiction, the parallels between them are so numerous that I could spend the rest of this review writing just about them.

But there are other reasons for my fascination with the film. Like me, Assayas was a film critic before turning to filmmaking. We share a longstanding interest in Taiwanese cinema and were both friends with the late director Edward Yang. Spending time with Assayas on a couple of occasions in the ‘90s, I found him smart and charming – he’s often compared to François Truffaut, another polemical Cahiers du Cinema editor turned celebrated auteur – yet Summer Hours is the first of his films that impresses me as much artistically as the man himself does personally and as a critic.

I’m tempted to say that, putting aside these various personal reasons for being attracted to Summer Hours, I find it the best foreign film released so far this year. But of course I can’t put aside those reasons or deny their influence, so I will offer that superlative with all subjective factors admitted, and give the film my highest possible recommendation.

The lovely house at the center of Summer Hours sits outside of Paris. It belongs to 75-year-old Hélène (Edith Scob), but it is more than just a family home; it is also something of a shrine to her uncle, Paul Berthier, a famous artist of the mid-20th century.

In the film’s first scene, a birthday gathering, we meet the whole family, including Hélène’s three children, all in their 40s. Frédéric (Charles Berling), the eldest, is an economist and teacher who lives in Paris; he’s married with two teenage kids. Adrienne (Juliette Binoche), who is single, is a designer based in New York. Jérémie (Jérémie Renier), a businessman, works in China and has a wife and three young children.

As we get to know Hélène in that initial scene, she tries to discuss with Frédéric what will happen to the house and its artistic treasures once she’s gone. “Change the subject,” he says, uncomfortable at the intimation of mortality. But her foresight is well-placed. Within a few months, she dies suddenly and her children are left having to decide how to deal with their inheritance.

Believe it or not, this is a French movie dealing with highly charged family issues and yet no one at any time screams, loses their temper or throws a wine glass! (In this, Assayas commendably bests his countryman Arnaud Desplechin, whose ridiculously overrated A Christmas Tale was full of such overheated histrionics.) In fact, the film is a model of subtlety and understatement, which makes it all the more believable and emotionally compelling.

It turns out the three siblings have two views of what should be done with their mother’s bequest. Frédéric assumes that they all will want to keep the house, use it for family gatherings in summer, and pass it on to their children. But Adrienne and Jérémie have to break it to him that they see things differently. They live too far away to visit the house much, and both could use the money. They are for selling.

The crux here is not that one viewpoint is right and the other not, but that time inevitably brings the dissolution of family bonds and ties to tradition, no matter what is decided. Before she dies, Hélène remarks that when she passes, various things will be unavoidably be lost: memories, secrets and so forth. The film’s lyrical, gently elegiac yet ultimately clear-eyed approach perfectly captures the bittersweet truth of her comment.

Much of this story’s emotional content attaches to the house itself, and the film effectively gives us two “tours” in scenes which ingeniously and evocatively mirror each other. The first is the opening scene mentioned above. Brushing away Frédéric’s suggestion that she change the subject, his mother leads him through the house, commenting on its valuable furniture and artworks. Just as the light filtering in from outside has a summery glow, Hélène’s remarks about these object are full of the warmth of love and familiarity.

The second scene comes months later, when Frédéric and Adrienne are showing appraisers around the house. It is now winter, the light seems cold and stark, and there’s a similar coldness to the way the artworks and household objects are now scrutinized for their monetary value alone.

Besides their dramatic content, these scenes are notable for the expressive elegance of Assayas’ visual style. He has always been a devotee of camera movement, but nothing here is frenetic or showy. Rather, in ways that suggest a combination of Jean Renoir and Robert Altman, the camera elegantly surveys the house and its contents with constant, understated movements and re-framings that continually unfold new perspectives on the emotional dimensions of the home and its contents.

Assayas is similarly adept with his cast. Berling, Binoche and Renier are all terrific actors and their performances here are among the most finely shaded and engaging that I’ve seen in any recent movie.

Late in the film, Frédéric sees some of Hélène’s cherished artworks on display in a museum. He remarks that they now seem “disenchanted.” The whole movie is contained in that one word: This tale is about the disenchantment that time’s inexorable progress brings. Yet there is no anger or bitterness in the way Summer Hours evokes this process; the film is simply too wise for that.

Like Moving Midway, Summer Hours has evoked comparisons to The Cherry Orchard. Its themes and stylistic nuance also suggest the influence of the Japanese master Yasujiro Ozu and Assayas’ Taiwanese friend Hou Hsiao-hsien. Yet the film finally is a wonderful, hugely impressive original, proof of the confident mastery that Olivier Assayas has attained.